A sidecar for your service mesh

- Abhishek Tiwari

- Research

- 10.59350/89sdh-7xh23

- Crossref

- June 23, 2017

Table of Contents

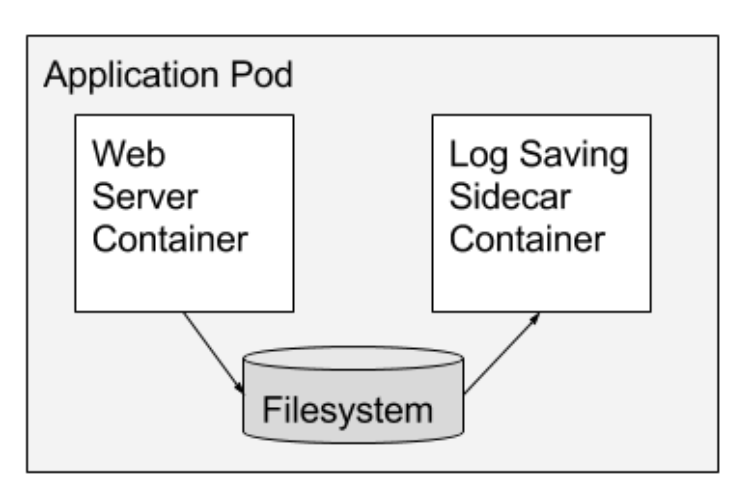

In a recent blog post, we discussed object-inspired container design patterns in detail and the sidecar pattern was one of them. In a sidecar pattern, the functionality of the main container is extended or enhanced by a sidecar container without strong coupling between two. This pattern is particularly useful when using Kubernetes as container orchestration platform. Kubernetes uses Pods. A Pod is composed of one or more application containers. A sidecar is a utility container in the Pod and its purpose is to support the main container. It is important to note that standalone sidecar does not serve any purpose, it must be paired with one or more main containers. Generally, sidecar container is reusable and can be paired with numerous type of main containers.

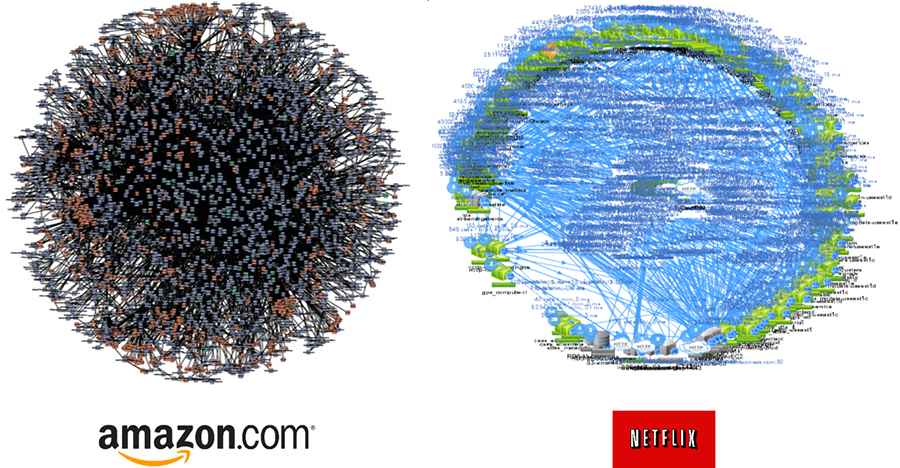

Service mesh

A service mesh is a dedicated infrastructure layer for handling service-to-service communication and global cross-cutting of concerns to make these communications more reliable, secure, observable and manageable. This dedicated layer of infrastructure combined with service deployments is commonly referred to as a service mesh. If you have a few microservices then service mesh could be an overkill but if you have a network of microservices (100s or 1000s of them) as illustrated below then service mesh is quite essential.

In the context of the microservices architecture and service-to-service communication, the term service mesh is relatively new but a similar concept circuit breaker existed before. The roots of service mesh models can be traced back to microservice sidecars and proxy frameworks like Netflix’s Prana, Airbnb’s SmartStack and Lyft’s Envoy.

Fault tolerance libraries

Circuit breakers have been extensively used to prevent a network or service failure from cascading to other services. Fault tolerance libraries such as Twitter’s Finagle, and Netflix’s Hystrix offered implementation of the circuit breaker pattern.

The basic idea behind the circuit breaker is very simple. You wrap a protected function call in a circuit breaker object, which monitors for failures. Once the failures reach a certain threshold, the circuit breaker trips, and all further calls to the circuit breaker return with an error, without the protected call being made at all. Usually, you’ll also want some kind of monitor alert if the circuit breaker trips. - Martin Fowler

In many ways, fault tolerance libraries were first service meshes. Strong coupling is one of the big drawbacks for these fault tolerance libraries. For instance, application code has to either extend or use primitives from these libraries. Moreover one has to use specific languages (Java/Scala) or frameworks or application server (Tomcat/Jetty) to implement them.

Unlike fault tolerance libraries, service mesh decouples application code from the management of service-to-service communication. The application code doesn’t need to know about network topology, service discovery, load balancing and connection management logic.

Service mesh frameworks

At this stage, Istio and Linkerd are two key production ready service mesh frameworks. Both Istio and Linkerd are open-source projects and designed for cloud-native microservices. Istio uses Lyft’s Envoy 1 2 as an intelligent proxy deployed as a sidecar. Linkerd is built on top of Netty and Finagle. Both frameworks support dynamic routing, service discovery, load balancing, TLS termination, HTTP/2 & gRPC proxying, observability, policy enforcement, and many other features.

Service mesh deployment models

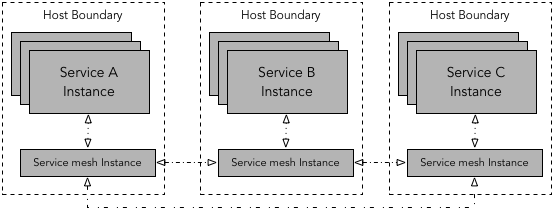

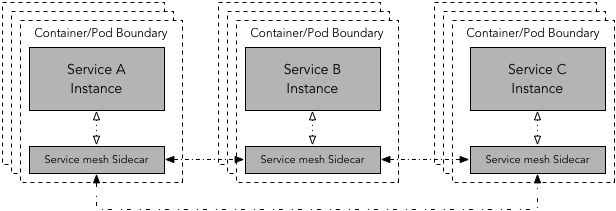

Service mesh can be deployed in two different patterns: (1) per-host proxy deployment and, (2) sidecar proxy deployment. For Istio, Envoy is generally deployed as sidecar proxy but it can also be deployed on a per-host proxy pattern. In the case of Linkerd, linkerd (Finagle + netty) can be deployed either as proxy instance or sidecar. Istio currently runs only on Kubernetes, whereas Linkerd can run on Kubernetese, DC/OS, and a cluster of host machines.

In per-host proxy deployment pattern, one proxy is deployed per host. A host can be a virtual machine, or a physical host or a Kubernetes worker node. Multiple instances of application services run on the host. All application services on a given host route traffic through this one proxy instance. In the case of Kubernetes, the proxy instance can be deployed as daemonset.

In sidecar proxy deployment pattern, one sidecar proxy is deployed per instance of every service. This model is particularly useful for deployments that use containers or Kubernetes. In the case of Kubernetes, a service mesh sidecar container can be deployed along with application service container as part of the Kubernetes Pod. Obviously, sidecar approach requires more instances of the sidecar, hence a smaller resource profile for sidecar is usually appropriate. If resource profile is an issue, as mentioned above, by deploying service mesh instance as a daemonset, we can reduce the number of service mesh containers to one per-host instead of one per pod.

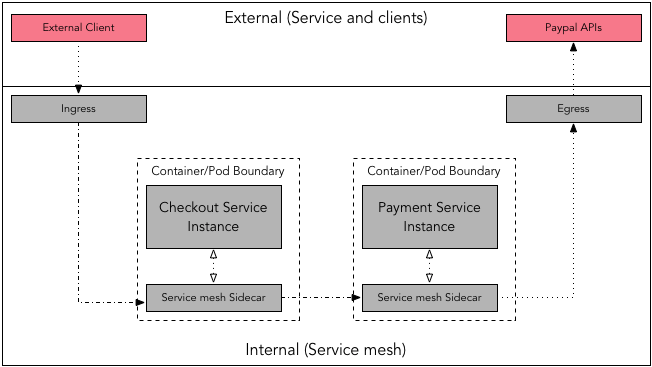

By default, proxies handle only intra-service mesh cluster traffic - between the source (upstream) and the destination (downstream) services. To expose a service which is part of service mesh to outside word, you have to enable ingress traffic. Similarly, if a service depends on an external service you may require enabling the egress traffic.

Checkout Service via ingress, which then invokes Payment Service. Payment Service depends on external service Paypal APIs to process the actual payment which is routed through the egress.Service-to-service communication

One of the core components of any mesh framework is service-to-service communication. To enable service-to-service communication a service mesh framework offers following key features,

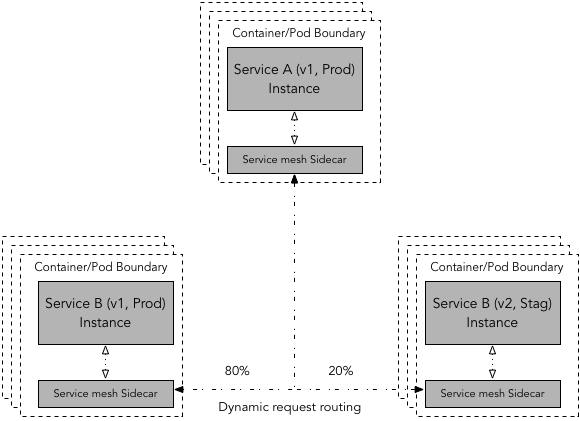

Dynamic request routing

In a service mesh implementation, dynamic request routing enables request to be routed to a specific version of service (v1, v2, v3) in the given environment (dev, stag, prod) using routing rules. The actual implementation of dynamic request routing and routing rules may vary 3 4 between different service mesh frameworks but basic mechanics remains same - a source service requests to a target service, exact version of target service is determined by service mesh instance by looking up routing rules. Dynamic request routing also helps with traffic shifting for common deployment scenarios such as blue-green deploys, Canary, A/B testing, etc.

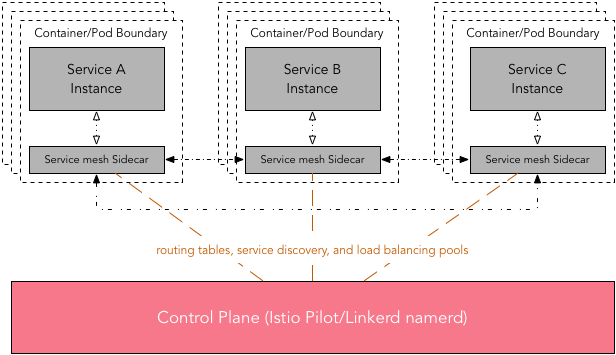

Control Plane

Due to distributed nature of service mesh, a control plane or a similar centralized management utility is desirable. This utility helps in the management of routing tables, service discovery, and load balancing pools. In Istio it is called as control plan which consists of three key components Pilot, Mixer, Istio-Auth. In Linkerd, namerd 5 is a centralized service that manages to routing tables and service discovery. It achieves this by storing routing rules in dtabs 5 and using namers 5 for service discovery.

Obviously, any comparison between the Istio control plane with Linkerd’s namerd will be like comparing apple with orange. Nonetheless, Istio control plane is more feature rich and offers a lot more functionalities than namerd. For instance, with help of Mixer and Istio-Auth control plane enables service-to-service and end-user authentication, enforcing access control and usage policies across the service mesh.

Service discovery and load balancing

Service discovery helps to discover the pool of instances of a specific version of service in a particular environment and update the load balancing pools accordingly. Both Istio (by virtue of Envoy’s features) and Linkerd (by inherited Finagle’s features) support several sophisticated load balancing algorithms 6. In addition, linkerd provides failure- and latency-aware load balancing that can route around slow or broken service instances. With Envoy, failure-aware load balancing is implemented differently i.e. when health check failures for a given instance exceeds a pre-specified threshold, it will be ejected from the load balancing pool.

Istio vs. Linkerd

| Features | Istio | Linkerd |

|---|---|---|

| Proxy | Envoy Proxy | Finagle + Jetty |

| Circuit Breaker | Enforces circuit breaking limits at the network level; circuit breaker can be set based on a number of criteria such as connection and request limits. | The two types of circuit breaking: (1) Fail Fast - a session-driven circuit breaker, and (2) Failure Accrual - a request-driven circuit breaker |

| Dynamic Request Routing | Fine-grained dynamic request routing to service instances by versions or environment; | Service destination (service name) and the concrete destination (version and environment) to allow dynamic request routing |

| Traffic Shifting/Splitting | Yes;shift traffic in an incremental and controlled way. | Yes;shift traffic in an incremental and controlled way. |

| Service Discovery | Provides a platform-agnostic service discovery interface; Consumes information from the service registry | Uses namer for service discovery which ships with a simple file-based service discovery mechanism but can also work with Zookeeper, Consul, Kubernetes |

| Load Balancing | Support several sophisticated load balancing algorithms provided by Envoy; Eject unhealthy service instance from the load balancing pool | Support several Finagle’s load balancing algorithms; provide failure- and latency-aware load balancing |

| Security | Securing end-user to service communication and service-to-service communication; Key management using per-cluster CA; Planned End-user to service authentication | Easy to add TLS to all service-to-service calls; Per-service or per-environment certificates; Key management involved process |

| Access Control | Enforce simple whitelist- or blacklist-based access control; Enforce quotas and rate limits | - |

| Observability | Metrics (Prometheus, statsd); Monitoring (New Relic, Stackdriver); Logging (Application and Access logs); Distributed tracing (Zipkin) | Distributed tracing (Zipkin); Metrics (InfluxDB, Prometheus, statsd) |

| Deployment Support | Kubernetes; Sidecar proxy | Kubernetes, Mesos, Cluster of hosts; Per-host or sidecar proxy |

| Control Plane | Pilot, Mixer, Istio-Auth | namerd |

| Service-to-service Communication | HTTP1.1 or HTTP/2, gRPC or TCP, with or without TLS | HTTP1.1 or HTTP/2, gRPC or TCP, with or without TLS |

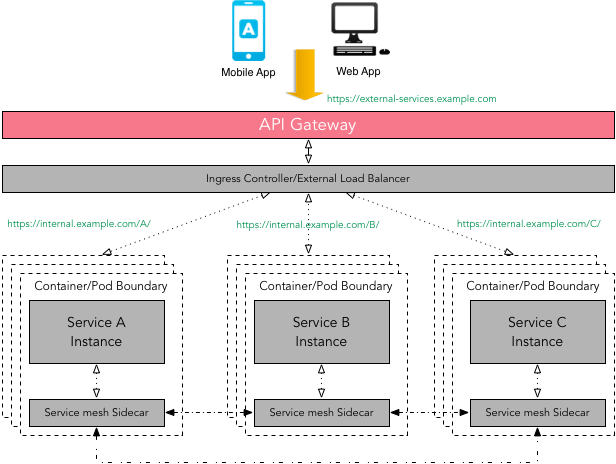

API Gateway vs. Service mesh

There is definitely some overlap between API Gateway and Service mesh patterns i.e. request routing, composition, authentication, rate limiting, error handling, monitoring, etc. As a case in point, one of the open source API Gateway - Ambassador uses Envoy for the heavy lifting. Given the use of Envoy, there’s a good amount of overlap between Ambassador and Istio. That said, the primary focus of a service mesh is service-to-service communication (internal traffic), whereas an API Gateway offers a single entry point for external clients such as a mobile app or a web app used by end-user to access services (external traffic).

Technically one can use API Gateway to facilitate internal service-to-service communication but not without introducing the latency and performance issues. As the composition of services can change over time and should be hidden from external clients - API Gateway makes sure that this complexity is hidden from the external client. It is important to note that a service mesh can use a diverse set of protocols (RPC/gRPC/REST), some of which might not be friendly to external clients. Again, API Gateway can handle multiple types of protocols and if can support protocol translation if required. There is no reason why one can not use API Gateway in front of a service mesh 7 - that’s exactly what we should be doing as a best practice.

Envoy is written in C++ and it is small, lightweight L7 proxy and communication bus ↩︎

In addition to this blog post, I will highly recommend going through a series of posts published by Christian Posta on Envoy sidecar proxy ↩︎

Envoy Load balancing algorightms and Load balancing in Linkerd ↩︎

Enabling Ingress Traffic - how to configure Istio to expose a service outside of the service mesh cluster ↩︎